I pay tribute to the late outstanding architectural critic and Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Ada Louise Huxtable. She upheld architectural beauty in a world of so many tasteless and uncultured monstrosities. We need more people like her in this world, especially in the booming cities of Asia which shouldn't blindly mirror the numerous garish and soul-less urban horrors or excesses of the West. We in Asia should celebrate the architectural uniqueness of our Eastern civilizations through balanced and ecological urban planning, by upholding elegance, beauty, culture and even spirituality in our architectures.

(Image below sourced from berkshirefinearts.com)

(Image below sourced from metropolismag.com)

Below is an obituary article from her former newspaper, The New York Times:

Ada Louise Huxtable, Champion of Livable Architecture, Dies at 91

(Image below sourced from berkshirefinearts.com)

(Image below sourced from metropolismag.com)

Below is an obituary article from her former newspaper, The New York Times:

Ada Louise Huxtable, Champion of Livable Architecture, Dies at 91

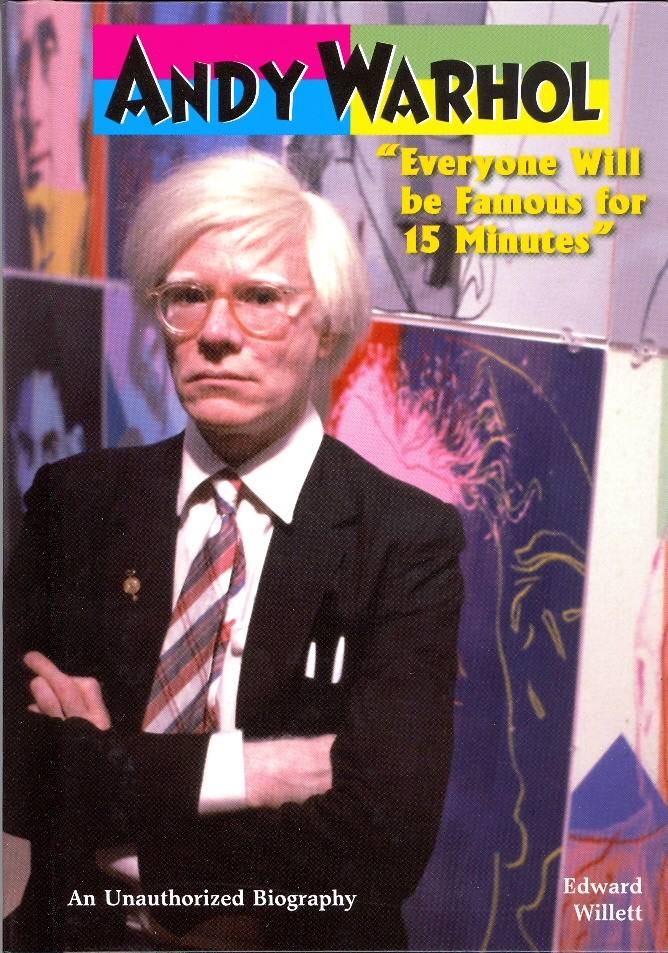

Librado Romero/The New York Times

Ada Louise Huxtable, with Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, in 1970, when she won the first Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism.

By DAVID W> DUNLAP, The New York Times

Published: January 7, 2013

Ada Louise Huxtable, who pioneered modern architectural criticism in the pages of The New York Times, celebrating buildings that respected human dignity and civic history — and memorably scalding those that did not — died on Monday in Manhattan. She was 91.

Her lawyer, Robert N. Shapiro, confirmed her death. She lived in Manhattan and Marblehead, Mass.

Beginning in 1963, as the first full-time architecture critic at an American newspaper, she opened the priestly precincts of design and planning to everyday readers. For that, she won the first Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism, in 1970. More recently, she was the architecture critic of The Wall Street Journal.

“Mrs. Huxtable invented a new profession,” a valedictory Times editorial said in 1981, just as she was leaving the newspaper, “and, quite simply, changed the way most of us see and think about man-made environments.”

At a time when architects were still in thrall to blank-slate urban renewal, Ms. Huxtable championed preservation — not because old buildings were quaint, or even necessarily historical landmarks, but because they contributed vitally to the cityscape. She was appalled at how profit dictated planning and led developers to squeeze the most floor area onto the least amount of land with the fewest public amenities.

She had no use for banality, monotony, artifice or ostentation, for private greed or governmental ineptitude. She could be eloquent or impertinent, even sarcastic. Gracefully poised in person, she did not shy in print from comparing the worst of contemporary American architecture to the totalitarian excesses of Hitler, Mussolini and Stalin.

“You must love a country very much to be as little satisfied with it as she,” Daniel Patrick Moynihan, later a United States senator from New York, wrote in his preface to a 1970 collection of Ms. Huxtable’s writings, “Will They Ever Finish Bruckner Boulevard?”

It was the first of several books whose titles alone conveyed her impatient, irreverent tone. These included “Kicked a Building Lately?” (1976) and “Goodbye History, Hello Hamburger” (1986).

Though knowledgeable about architectural styles, Ms. Huxtable often seemed more interested in social substance. She invited readers to consider a building not as an assembly of pilasters and entablatures but as a public statement whose form and placement had real consequences for its neighbors as well as its occupants.

“I wish people would stop asking me what my favorite buildings are,” Ms. Huxtable wrote in The Times in 1971, adding, “I do not think it really matters very much what my personal favorites are, except as they illuminate principles of design and execution useful and essential to the collective spirit that we call society.

“For irreplaceable examples of that spirit I will do real battle.”

Actually, there was no mistaking what Ms. Huxtable liked — Lever House, the Ford Foundation Building and the CBS Building in Manhattan; the landmark Bronx Grit Chamber; Boston’s City Hall; the East Building of the National Gallery of Art in Washington; Pennzoil Place in Houston — and, even more delectably, what she did not.

“The new museum resembles a die-cut Venetian palazzo on lollipops,” she wrote in 1964 about the Gallery of Modern Art at 2 Columbus Circle. Her description came to be synonymous with the structure itself, “the lollipop building,” and was probably more familiar to New Yorkers than the name of the architect: Edward Durell Stone.

The long-abandoned gallery has since been substantially altered as the Museum of Arts and Design. It might be argued that Ms. Huxtable’s lollipop epithet helped doom preservationists’ later efforts to save the original facade. But Mr. Stone’s romantic brand of monumental modernism was never to her liking.

“Albert Speer would have approved,” she said in 1971 about his Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, linking Mr. Stone indirectly to the Nazis’ chief architect. “The building is a national tragedy. It is a cross between a concrete candy box and a marble sarcophagus in which the art of architecture lies buried.”

This was a far cry from the fawning coverage of new buildings that Ms. Huxtable deplored in the newspapers of the 1950s. And it was welcomed.

Ada Louise Landman was born on March 14, 1921, to Leah Rosenthal Landman and Dr. Michael Louis Landman. She grew up in Manhattan in a Beaux-Arts apartment house, the St. Urban, at Central Park West and 89th Street, and wandered enthralled through Grand Central Terminal, the Museum of Natural History and the Metropolitan Museum.

She attracted notice in The Times at an early age with her stage-set designs for Hunter College productions of “The Yellow Jacket” in 1940 and “H.M.S. Pinafore” in 1941. After graduating from Hunter in 1941, she attended New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts. But her most treasured academic home was probably the Avery Architectural Library at Columbia University.

Out of school, she was hired by Bloomingdale’s to sell a furniture line with works by Eero Saarinen and Charles Eames. “Many young architects and designers made the obligatory tour of the rooms,” she recalled. “One of them noticed and married me.”

That was L. Garth Huxtable, an industrial designer. He took many of the photographs that illustrated his wife’s books. The couple also collaborated in designing tableware for the Four Seasons restaurant, which opened in 1959 in the Seagram Building. Mr. Huxtable died in 1989. Ms. Huxtable left no immediate survivors.

Ms. Huxtable was assistant curator of architecture and design at the Museum of Modern Art from 1946 to 1950. She was a Fulbright fellow, studying Italian architecture and design in 1950-52, and a Guggenheim fellow in 1958. She had also begun writing for architectural journals.

In 1958 she addressed a broader audience in The New York Times Magazine with an article criticizing how newspapers covered urban development. “Superblocks are built, the physiognomy and services of the city are changed, without discussion,” Ms. Huxtable wrote. “Architecture is the stepchild of the popular press.”

Five years later she was invited to become a critic by Clifton Daniel, then assistant managing editor of The Times. Though architectural commentary was not new — a line could be traced, largely in magazines, to the 19th century through Aline B. Saarinen, Lewis Mumford, Montgomery Schuyler and others — Ms. Huxtable was being asked to write full time for a general-interest newspaper.

“At first she turned him down, saying daily journalism would disrupt her private life,” Nan Robertson wrote in her 1992 book “The Girls in the Balcony: Women, Men and The New York Times.” “Daniel looked elsewhere, assiduously, but in his own words, ‘I couldn’t find anyone better than she was.’ ”

Ms. Robertson said Ms. Huxtable followed in the tradition of the foreign affairs columnist Anne O’Hare McCormick: “so good they could not be ignored by the men who ran the establishment, and so personally assertive that they would not be ignored.”

For her part Ms. Huxtable said The Times made a “brave gamble” in the “belief that the quality of the built world mattered, at a time when environment was still only a dictionary word.”

Feared by some architects, loathed by some developers and not universally admired by scholars, Ms. Huxtable was nonetheless “a darling of the public,” Robert A. M. Stern, Thomas Mellins and David Fishman wrote in “New York 1960,” published in 1995.

Her exacting standards were well enough known to be a punch line for a New Yorker cartoon by Alan Dunn in 1968. It shows a construction site so raw that only a single steel column has been erected. A hard-hat worker holding a newspaper tells the architect, “Ada Louise Huxtable already doesn’t like it!”

In 1969 the Pulitzer Prizes were expanded to include an award for distinguished criticism or commentary.

The first, in 1970, was split by the judges between Ms. Huxtable for criticism and Marquis W. Childs of The St. Louis Post-Dispatch for commentary. She was the second woman, after Mrs. McCormick, 33 years earlier, to win a Pulitzer for The Times. In 1973 she was the second woman ever named to the Times editorial board. (Mrs. McCormick had been the first.) She was succeeded as the daily architecture critic by Paul Goldberger but continued to write about architecture in a Sunday column. She left The Times when she was appointed a MacArthur Fellow in 1981. In her wake, architectural criticism became a staple at big newspapers and grist for subsequent Pulitzer Prizes.

“Before Ada Louise Huxtable, architecture was not a part of the public dialogue,” Mr. Goldberger said in 1996.

Ms. Huxtable was the author of 11 books. “Four Walking Tours of Modern Architecture in New York City” (1961), included a characteristic critique of the Pan Am Building, which was then being built directly behind Grand Central. (It is now the MetLife Building.)

Rather than aesthetics, Ms. Huxtable focused on how the tower would alter the scale of Park Avenue, adding “an extraordinary burden to existing pedestrian and transportation facilities.” She continued, “Its antisocial character directly contradicts the teachings of Walter Gropius, who has collaborated in its design.”

When The Times named her a critic, Ms. Huxtable was working on a six-volume series on New York City architecture. Only the first volume, “Classic New York: Georgian Gentility to Greek Elegance,” was published, in 1964.

In it, she extolled not just lovely Greek Revival temples but also mongrelized houses from the early 1800s.

“They rank as ‘street architecture’ rather than as ‘landmarks,’ ” she said. “Their value is contrast, character, visual and emotional change of pace, a sudden sense of intimacy, scale, all evocative qualities of another century.”

Her interest in preservation did not make her an enemy of modernity. In “The Tall Building Artistically Reconsidered: The Search for a Skyscraper Style” (1984), Ms. Huxtable said the glass curtain-wall skyscraper, epitomized by the work of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, offered “a superb vernacular, probably the handsomest and most useful set of architectural conventions since the Georgian row house.”

What infuriated her were “authentic reproductions” of historical architecture and “surrogate environments” like Colonial Williamsburg and master-planned communities like the Disney Company’s Celebration, Fla. “Private preserves of theme park and supermall increasingly substitute for nature and the public realm, while nostalgia for what never was replaces the genuine urban survival,” she wrote in “The Unreal America: Architecture and Illusion” (1997).

Ms. Huxtable’s last book, in 2008, was “On Architecture: Collected Reflections on a Century of Change.” And her last column, published in The Journal on Dec. 3, 2012, concerned the impending reconstruction of the New York Public Library eliminating the central stacks. Typically enough, it was titled, “Undertaking Its Destruction.”

Ultimately, however, what animated and sustained her were not the mistakes but the triumphs. As she said of New York City in The Times in 1968:

“When it is good, this is a city of fantastic strength, sophistication and beauty. It is like no other city in time or place. Visitors and even natives rarely use the words urban character or environmental style, but that is what they are reacting to with awe in the presence of massed, concentrated, steel, stone, power and life.”