One reason to visit New York City! One of the exhibits in the Jewish Museum New York titled "Crossing Borders: Manuscripts from the Bodleian Libraries" (Sept. 14, 2012 - Feb. 3, 2013)

My Comments:

I'm in awe and very impressed with this exhibit on books, especially in this modern 21st century era when the popularity of ebooks, social media, computer games, 24-hour cable TV channels, online movies, texting and shopping malls try to make reading of books less of a pastime than it used to be. I love books!

Over 50 manuscripts, many of them illuminated, from the famous Bodleian Libraries at Oxford, highlight "the role of Hebrew books as a meeting place of cultures in the Middle Ages".

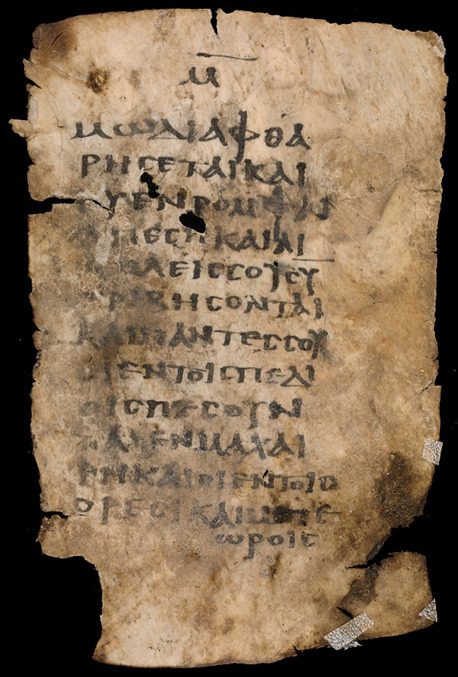

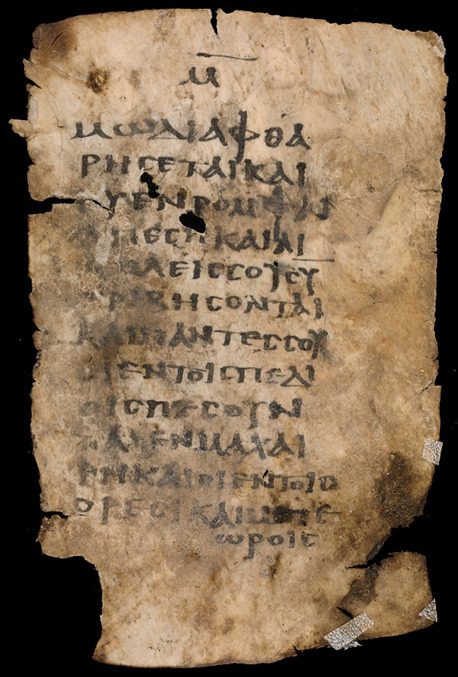

There is even the "Mishneh Torah" of Maimonides written in his own hand! Egypt, circa year 1180, found in the Cairo Genizah, 9 1/4 x 6 1/2 inches (23.5 x 16.5 centimeters), MS. Heb. d. 32, fols. 53b-54a.

This is a draft of a portion of the Book of Civil Laws, a section of the "Mishneh Torah" of Maimonides (1135– 1204), written in his own hand. The philosopher and royal physician wrote his masterpiece on rabbinic law in Hebrew, whereas his earlier works had been composed in Judeo-Arabic (Arabic in Hebrew characters). Maimonides’s cursive Sephardic script is similar to contemporary Arabic script. The pages seen below deal with the laws of hiring (right) and the laws of borrowed and deposited things (left). See image below:

Many of these amazing and ancient books are on exhibit in the United States for the first time.

Address of Jewish Museum: 1109 5th Ave at 92nd Street, New York City, New York 10128, USA

Free entrance on Saturdays because of the Jewish Sabbath, a day of rest and a special time for spiritual enrichment free from the concerns of schedules, everyday work and commerce

(Below) Kennicott Bible, scribe: Moses ibn Zabara, artist: Joseph ibn Hayyim, commissioner: Isaac, son of Solomon di Braga, Corunna, Spain, 1476.Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, MS.

Kennicott 1, fol. 7b

My Comments:

I'm in awe and very impressed with this exhibit on books, especially in this modern 21st century era when the popularity of ebooks, social media, computer games, 24-hour cable TV channels, online movies, texting and shopping malls try to make reading of books less of a pastime than it used to be. I love books!

Over 50 manuscripts, many of them illuminated, from the famous Bodleian Libraries at Oxford, highlight "the role of Hebrew books as a meeting place of cultures in the Middle Ages".

There is even the "Mishneh Torah" of Maimonides written in his own hand! Egypt, circa year 1180, found in the Cairo Genizah, 9 1/4 x 6 1/2 inches (23.5 x 16.5 centimeters), MS. Heb. d. 32, fols. 53b-54a.

This is a draft of a portion of the Book of Civil Laws, a section of the "Mishneh Torah" of Maimonides (1135– 1204), written in his own hand. The philosopher and royal physician wrote his masterpiece on rabbinic law in Hebrew, whereas his earlier works had been composed in Judeo-Arabic (Arabic in Hebrew characters). Maimonides’s cursive Sephardic script is similar to contemporary Arabic script. The pages seen below deal with the laws of hiring (right) and the laws of borrowed and deposited things (left). See image below:

Many of these amazing and ancient books are on exhibit in the United States for the first time.

Address of Jewish Museum: 1109 5th Ave at 92nd Street, New York City, New York 10128, USA

Free entrance on Saturdays because of the Jewish Sabbath, a day of rest and a special time for spiritual enrichment free from the concerns of schedules, everyday work and commerce

(Below) Kennicott Bible, scribe: Moses ibn Zabara, artist: Joseph ibn Hayyim, commissioner: Isaac, son of Solomon di Braga, Corunna, Spain, 1476.Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, MS.

Kennicott 1, fol. 7b

The New York Times newspaper's Exhibition Review

What Books Said to One Another

‘Crossing Borders’ Opens at the Jewish Museum

Lauren Lancaster for The New York Times

Crossing Borders A 15th-century book showing the Virgin riding a unicorn in this show at the Jewish Museum.

By EDWARD ROTHSTEIN

Published: September 14, 2012

If you listen closely at the subtly startling new exhibition at the Jewish Museum, “Crossing Borders: Manuscripts From the Bodleian Libraries,” you can hear manuscripts murmuring across millenniums.

Lauren Lancaster for The New York Times

Books of many eras displayed in vitrines at the exhibition “Crossing Borders: Manuscripts From the Bodleian Libraries,” at the Jewish Museum.

Some defer to others: they are commenting on sacred texts. Some supplant others: sacred texts of one faith argue against those of another. But, as presented here, many also engage in unexpected dialogues, emulations, even dissections. Scripts imitate one another, even if they are in different languages; images and designs recur in manuscripts from different conceptual worlds. Some texts remain unflustered while everything changes around them. And all of this takes place among just 52 works, some of which are astonishingly ancient, many of which are beautifully illuminated, and most of which are written in Hebrew.

It would be a challenge just to give individual items the attention they demand, let alone attend to their interactions: a third-century fragment of papyrus with Philo of Alexandria’s interpretation of scripture; a fifth-century codex of the Four Gospels written in the ancient Aramaic dialect Syriac; a 12th-century autograph manuscript of legal commentary written in Arabic by the Jewish scholar Maimonides using Hebrew letters; a 16th-century Persian Koran with exquisite decoration; a 16th-century Hebrew poem written for Queen Elizabeth I, urging her to support Hebrew scholarship at the University of Oxford, as had her father, King Henry VIII.

It all comes from the Bodleian Libraries at Oxford, which has one of the world’s most important collections of Hebrew manuscripts. These examples were first gathered in 2009 for an exhibition at Oxford called “Crossing Borders: Hebrew Manuscripts as a Meeting-Place of Culture.” Its curators, Piet van Boxel and Sabine Arndt (who also edited an informative catalog), suggested that as exiled Jews established communities in vastly different cultures, their manuscripts both reflected the world around them and influenced it in unusual ways. Even when the texts themselves were relatively unchanging, their script and illumination testified to a dynamic, shifting relationship to the dominant cultures and religions of Christianity and Islam.

The curator at the Jewish Museum, Claudia Nahson, uses most of the same material but organizes it slightly differently to highlight the multilingual conversation, forming a capsule history of a people’s textual sojourn. The manuscripts have also been hauntingly mounted by the exhibition designer, MESH Architectures, in vitrines, each illuminated by beams from LEDs projected down, so that when a visitor looks across the galleries, the open codices seem to hover against the deep red walls, a sensation at once reverential and elevating. (MESH also designed the show’s rich Web site: bodleian.thejewishmuseum.org.)

There are some problems that come up, but the overall impact is powerful, with each display creating a miniature colloquy among texts. In some of the earliest material, for example, we see a vertical Hebrew scroll (a “rotulus”) of the 10th or early 11th century. But by that time, we learn, another form of textual presentation had become dominant: the codex, which is close in form to our printed books. And, indeed, the other items in the case, though older than the rotulus, are from codices.

Why were Hebrew codices so late in appearing? In the catalog the scholar Anthony Grafton suggests it may have been deliberate, perhaps to emphasize religious differences, particularly since the codex had become widely used as a portable means of proselytizing for Christianity.

But elsewhere in the exhibition, imitation is more the rule than rejection. Biblical commentary by the 11th-century Jewish scholar Rashi influenced Christian texts, and we see a 13th-century Hebrew Psalter extensively annotated in Latin and French. We also see how Islamic decorative style affected Hebrew scripts and influenced illuminations of both the New Testament and the Hebrew Bible.

One of the most beautiful objects here — the show’s centerpiece — is the 922-page Kennicott Bible, “the most lavishly illuminated Hebrew Bible” to survive from medieval Spain. It was completed in 1476, less than 20 years before the expulsion of the Jews, and is so elaborate it almost undermines itself, a sacred text more enticing for its decoration and its encyclopedic embrace of Islamic, Christian and folk styles than for its content. Its entire text has been scanned and put online by the Jewish Museum; each of its pages can also be examined at the exhibition on a sequence of mounted iPads.

Other examples of transformations of religious symbols are fascinating. Three manuscripts here display a common Christian motif in 15th-century Italy: the Virgin with a unicorn on her lap, defending it from a hunter.

The unicorn had become a symbol of Christ, so the image was an allusion to the Incarnation. But even seemingly secular images of unicorn hunts could be seen as allegories of persecution. With its status as a targeted innocent, the unicorn also became a Jewish symbol, the hunt invoking another kind of persecution.

So when the first page of an elaborately illustrated 1472 Hebrew Bible from Italy includes an image of a woman with a unicorn, as well as an image of Adam and Eve about to eat from the forbidden tree, how is this to be interpreted? This is a manuscript with a considerable scholarly “apparatus,” including commentary and readings, meant, we are told, for a synagogue. Was a Christian illustrator of the Hebrew text engaging in a subtle polemic? Or had the symbols become so bipolar they could sustain incompatible meanings?

These are difficult matters, but the currents of cultural influence run through these texts. We see a 15th-century book of fables in Hebrew that is a 13th-century translation of an Arabic translation of a 4th-century Sanskrit source: a collection of stories about scheming jackals. It is adjacent to a 14th-century Arabic version of the fables from Syria, and a 15th-century printed book from Strasbourg that is a Latin translation of an early Hebrew translation of the Arabic. We learn, too, that such texts led to the development of original Hebrew stories during the same period.

And while examples of the transmission of knowledge during this era have become more familiar in recent years, there is still something uncanny about seeing three examples of Euclid’s “Elements” open to the same diagrams and proofs in 13th-century Arabic, 14th-century Hebrew and 13th-century Latin.

The final gallery here also begins to put the collection itself in context, another astonishing phenomenon: how English Protestants in the late 16th century established Hebrew as a central subject for study. Thomas Bodley, a Hebraist and humanist, re-established a library at Oxford that had been plundered and provided the foundation for its renowned holdings.

There is one issue that is missing here, though it would have been difficult to explore it without considerably more explanation (and perhaps other manuscripts). In the early examples of the influence of Hebrew commentary on Christian scholars, we see a bit of what was at stake in these cultural and religious interactions: religious reinterpretations had to be grounded in a thorough understanding. But then the show ends up paying very little attention to substance, focusing instead on similarities of style, script and image that lie more on the surface of these texts.

Such cosmetic resemblances encourage a sense of vague ecumenism. The interactions among the three religions were described as “practical cooperation” at Oxford and here as “intellectual exchange,” but we don’t really understand much more about the content behind the form.

When stylistic influences were present, for example, were there intellectual or religious transformations that accompanied them? Did beliefs change along with textual styles? What was the nature of the relations among these communities? Even the rise of Protestant Hebraism might have been explored more deeply. In a way, we are its heirs: early Puritan settlers imagined the New World’s possibilities through the imagery of the Hebrew Bible.

But this is also asking for far too much, as if we were seeking elaborate discourses instead of appreciating the muted conversations. An acknowledgment of the complexities would have sufficed. As for inspiring deeper inquiry, that, after all, is a measure of the exhibition’s success.